RESEARCH WITH VIDEO VOLUNTEERS

Video Volunteers’ (VV) missi on is to “empower marginalized communities through film.” They are one of the world’s largest community media organizations, focused on training and supporting a network of over 200 Community Correspondents (CCs) across India who annually produce over 1,000 films. VV connects these films with local, national and international policymakers to empower communities for change on a variety of important social topics. Remarkably, roughly 20% of the films made by VV’s network result in the intended social change.

on is to “empower marginalized communities through film.” They are one of the world’s largest community media organizations, focused on training and supporting a network of over 200 Community Correspondents (CCs) across India who annually produce over 1,000 films. VV connects these films with local, national and international policymakers to empower communities for change on a variety of important social topics. Remarkably, roughly 20% of the films made by VV’s network result in the intended social change.

I came to learn about VV in my job as Curriculum & Media Arts Coordinator at Gordon Parks High School (GPHS) where I hired a former VV employee, Neha Belvalkar, as an Artist-in-Residence. Artists-in-Residence were hired to bring civic engagement and visual storytelling skills into our school. This successful, but now de-funded program played a crucial role with our students as racially diverse, socially active co-teachers in classrooms and CEDS projects. After a couple months of hearing about the vision for curriculum we were developing at the school, Neha introduced me to VV’s website.

From a quick review of their online content, the similarity in mission/vision to GPHS and the clear depth of citizen journalism training, tools and guidance capacity inspired me to make contact and write three grant applications within the week. All three applications were funded, and in January of 2016, I traveled to India with my family as a Fulbright Scholar to learn more about VV’s processes and how they could be translated to CEDS approaches to curriculum. VV’s mission and results truly embody one of Gordon Parks’ most famous quotes: “I picked up a camera because it was my choice of weapons against what I hated most about the universe: racism, intolerance, poverty.”

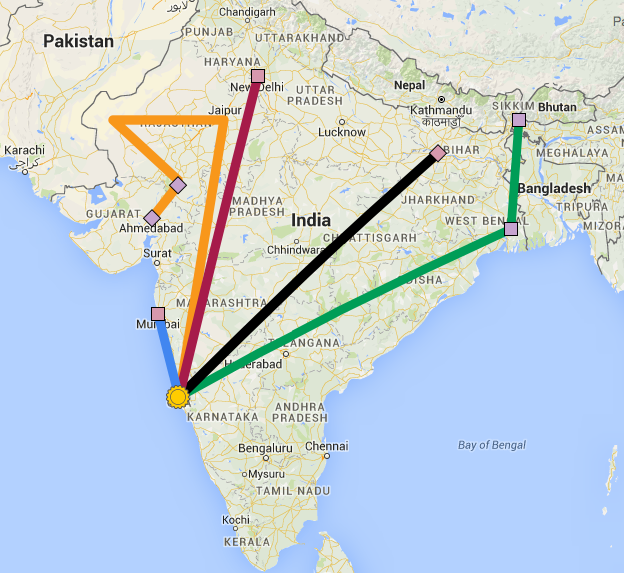

VV’s head office is located in Anjuna, Goa, bordering the Arabian Sea in Western India. Some 35 staff office in a tiled roof, Indo-Portuguese villa. From this office, VV organizes all CC trainings, mentorship, and provides support to correspondents located throughout India, has an editing team, conducts strategic networking and feeds a local yawning dog named Jogie, who serves as VV’s mascot and calls the office “home.” The place is a hive of activity each day, despite intermittent power outages and Internet lapses. The camaraderie is infectious, the vision clear, and the tangible goal of supporting CCs to empower Indian communities is a clear priority.

VV’s head office is located in Anjuna, Goa, bordering the Arabian Sea in Western India. Some 35 staff office in a tiled roof, Indo-Portuguese villa. From this office, VV organizes all CC trainings, mentorship, and provides support to correspondents located throughout India, has an editing team, conducts strategic networking and feeds a local yawning dog named Jogie, who serves as VV’s mascot and calls the office “home.” The place is a hive of activity each day, despite intermittent power outages and Internet lapses. The camaraderie is infectious, the vision clear, and the tangible goal of supporting CCs to empower Indian communities is a clear priority.

I wasn’t familiar with the term “community media” before I connected with VV. GPHS’ curriculum resembled community media in many ways, but we typically made the comparison to traditional journalism. Community media is different, and the distinctions open up significant possibilities for educators. Community media is sometimes referred to as “citizen journalism”, “solutions journalism”, or “citizen media.” All terms refer to a practice of purposeful community storytelling that empowers active citizenry to engage with the Democratic process. Community media organizations differ from mass media organizations in that they originate from and are highly accountable to the communities they serve, focus on the “how” and “why” of news events (as opposed to the “what, when and where”), and require/embed personal voice and perspective. These are some of the missing elements in today’s educational systems, and should be defining parts of future school curriculum. I began to believe VV’s community media trainings and processes are transferrable to schools that seek to integrate CEDS approaches to curriculum and make instruction more student and community relevant. GPHS had made progress on this integration, with eight years of struggle trying to institutionalize the systems needed to sustain these classroom experiences. VV’s well-honed training and support methods can become tools for educators.

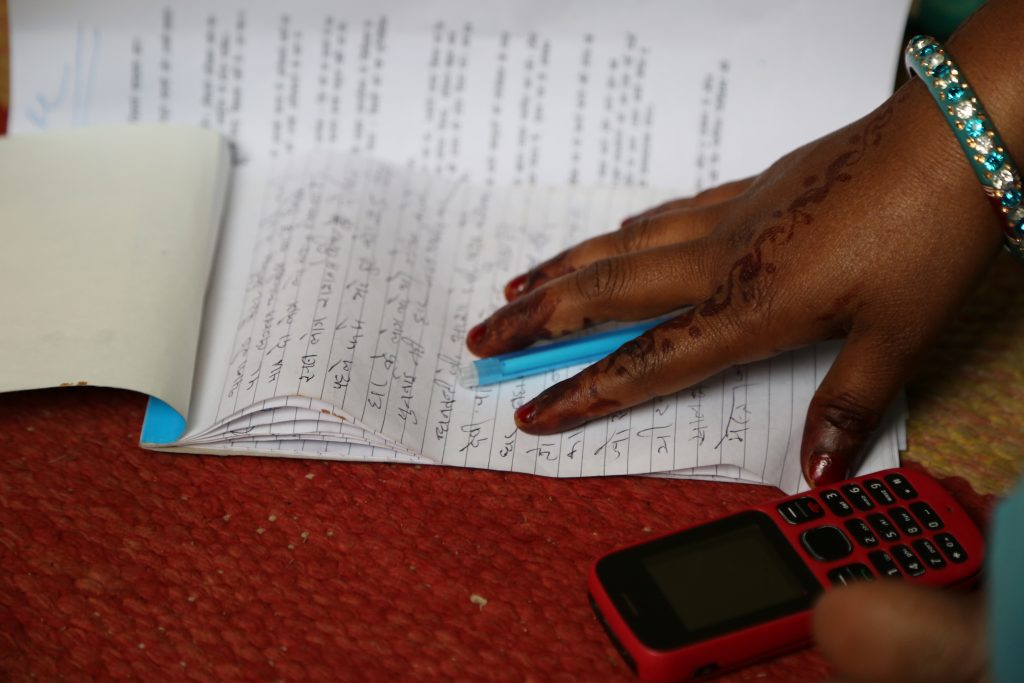

Young CCs from all  over India are the primary producers of Community Media for VV. They are typically 18-40 years old, from all cultural backgrounds, but primarily, highly marginalized tribal communities in rural India. These CCs typically have little to no filmmaking background and limited experience with technology before joining VV. In the words of first year CC Rebecca Parvin, age 20, “VV’s training makes citizen journalism easier for us.” They receive the trainings, confidence, vision and support to begin producing 1-2 films per month post training.

over India are the primary producers of Community Media for VV. They are typically 18-40 years old, from all cultural backgrounds, but primarily, highly marginalized tribal communities in rural India. These CCs typically have little to no filmmaking background and limited experience with technology before joining VV. In the words of first year CC Rebecca Parvin, age 20, “VV’s training makes citizen journalism easier for us.” They receive the trainings, confidence, vision and support to begin producing 1-2 films per month post training.

Through interviews and research at the Goa home office, I learned about the overarching structures of the training programs. VV divides their films into two categories: an Issue Film and an Impact Film. As their names imply, the Issue Film describes a social problem in the community, and the Impact Film tells the story of how a change occurred. The VV IndiaUnheard program manual further states “This is what distinguishes us from conventional journalism, which merely reports and then steps back from the situation. The purpose of community media is not to just to expose but help SOLVE these issues in a sustainable manner.” The filmmaking process and product are catalysts for the CC to empower community to articulate an Issue. The film also creates a medium to communicate with policy makers who are positioned to enact change. If change occurs, an Impact Film is made that documents the community effort, and the policymaker’s role in correcting the issue. Lines of communication are formed that have the potential to persist after the film is complete. An active citizenry increases in capacity to navigate future concerns. For an example Impact Film, click here for Bikash Barman’s MGNREGA backpay film.

In order to learn additional details and nuances of the trainings, I needed to see the trainings, and observe some of the existing CCs in action. So, I attended a CC field training on Impact Documentation in Patna, capital city of the northeastern state of Bihar, a training on Maternal Health in Malbazar, West Bengal, and a Community Media training at the TATA Institute of Social Sciences in Mumbai. I also participated in a workshop in Goa to provide film production support on smartphones and tablets. Along they way I also met with a few existing CCs in their towns and villages.

In order to learn additional details and nuances of the trainings, I needed to see the trainings, and observe some of the existing CCs in action. So, I attended a CC field training on Impact Documentation in Patna, capital city of the northeastern state of Bihar, a training on Maternal Health in Malbazar, West Bengal, and a Community Media training at the TATA Institute of Social Sciences in Mumbai. I also participated in a workshop in Goa to provide film production support on smartphones and tablets. Along they way I also met with a few existing CCs in their towns and villages.

At the field trainings, I observed the delivery of training curriculum, along with the instructional “soft skills” that VV trainers have honed over a decade. There are three main instructional elements: 1) technical filmmaking skills, 2) the corresponding writing and research processes required to produce and share a film, and 3) civic empowerment activities that encourage voice, leadership, action, and engaged Democratic citizenry.

VV teaches Community Media filmmaking techniques in a formulaic, understandable process using simple and rugged digital cameras. Their trainings separate films into four primary parts: Voice Over, B-Roll, Interview, P2C (Person 2 Camera). Trainings are visually rich, with numerous instructional video clips, and example films from other CCs who look and sound like those being trained.

Writing and research skill instruction are embedded within the visual storytelling and civic engagement process required to make an Issue or Impact Film. Trainers teach open-ended questioning, treatment writing, written storyboards, with particular emphasis on personal voice, perspective and engaging the “How and Why.” Trainers encourage an unlearning of “traditional” or mass media storytelling techniques. VV steers head on into these aspects of storytelling.

Writing and research skill instruction are embedded within the visual storytelling and civic engagement process required to make an Issue or Impact Film. Trainers teach open-ended questioning, treatment writing, written storyboards, with particular emphasis on personal voice, perspective and engaging the “How and Why.” Trainers encourage an unlearning of “traditional” or mass media storytelling techniques. VV steers head on into these aspects of storytelling.

This same encouragement of personal voice in filmmaking overflows into the thinking skills of civic empowerment and voice. What keeps us from engaging with the Democratic process after we’ve submitted our vote? Why are we assuming a particularly negative response from local policymakers when we haven’t yet spoken to them? How can we avoid a passive approach to community change? In order to create Community Media, rich with personal perspective, personal voice must be encouraged. A considerable degree of mental processing, research and listening must occur in order for a CC to propose consideration of the “How” and “Why” of the stories they cover. The VV training process “proves its salt” at these moments where high level sociological analysis intermixes with the nexus of world and local economics. The perspective of the CCs is imperative. CCs are the experts on the topics that inform their films, and their expertise is led through the reflection and empowerment process of all available academic domains: math, history, language arts, science, art. Filmmaking is a synthesizing activity, compatible with any subject area. One VV trainer called the process they embark on with CCs as “a two year journalism and two year Poli-Sci degree in four days!”

I observed VV trainings as an educator, noting the systems, strategies and soft skills that were used in hopes of translating them to educators interested connecting their students with similar rewarding results. Through the process I allowed myself the opportunity to reflect on my 18 years in public education, and the overarching and outdated system that ultimately dictates what can/can’t occur in classrooms. My hope is to offer a combination of broad system strategies and specific classroom solutions from this experience.

I observed VV trainings as an educator, noting the systems, strategies and soft skills that were used in hopes of translating them to educators interested connecting their students with similar rewarding results. Through the process I allowed myself the opportunity to reflect on my 18 years in public education, and the overarching and outdated system that ultimately dictates what can/can’t occur in classrooms. My hope is to offer a combination of broad system strategies and specific classroom solutions from this experience.

Social responsibility, creativity and authentic audience are the catalyzing and bonding agents that hold the VV films together. We live in communities. We have solutions. We want to be heard. The way that VV nurtures and supports CCs is rich and underutilized. Numerous aspects of VVs work creates learning opportunities for educators who seek to organize academic instruction and learning synthesis in a way that requires and propels student voice, engages with the core questions of “How” and “Why” in marginalized communities, and demands a vigorous creativity that has been stripped from modern education.

VV emphasizes that  they aren’t creating superheroes, but rather community leaders engaged with the Democratic process using storytelling to empower communities to unite their voices for change. At a 10-year regional development planning meeting in Panjim, I heard VV’s co-founder Stalin K. ask a community member “Do you find it easy to articulate your point to people?” “No” he replied. “Well that’s where Video Volunteers comes in.” VV has an impact across India, supporting the production of thousands of films on a variety of social welfare topics, articulating the sentiments of communities in need.

they aren’t creating superheroes, but rather community leaders engaged with the Democratic process using storytelling to empower communities to unite their voices for change. At a 10-year regional development planning meeting in Panjim, I heard VV’s co-founder Stalin K. ask a community member “Do you find it easy to articulate your point to people?” “No” he replied. “Well that’s where Video Volunteers comes in.” VV has an impact across India, supporting the production of thousands of films on a variety of social welfare topics, articulating the sentiments of communities in need.